In our very first statement on the lockdown, we noted the deep divisions within society that the coronavirus had laid bare. Following the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on Black, Asian and minority ethnic people, it is concerning that these very groups are not a higher priority for the vaccine rollout as access to this is only set to increase that divide.

With a death rate four times as high for Black people and three times as high for Asian people than their white counterparts, higher vulnerability due to the nature of the their job which are often frontline, and higher incidences of deprivation, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation should have highlighted these groups as top priority groups. Despite all the evidence, a decision was made to omit these communities in the initial vaccine priority list. The list has since been updated and on 30th December 2020, JCVI’s list included ‘mitigating inequalities’.

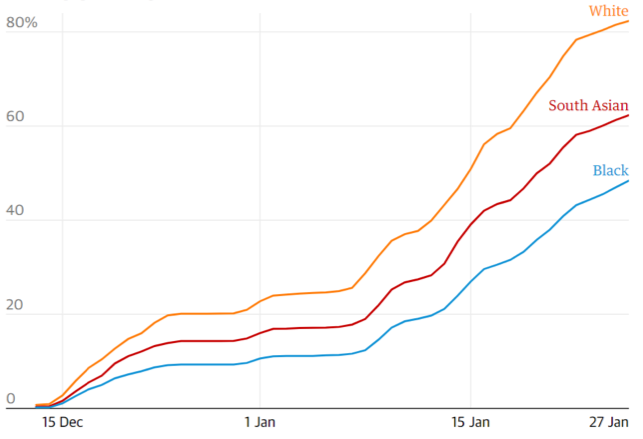

Share of population aged 80+ to have received at least one vaccine dose (Source: OpenSAFELY via the Guardian)

Researchers monitored the vaccination status of more than 1 million people aged 80 and over from the start of the vaccination programme on 8 December and found that vaccine coverage was twice as high among white people than Black people in the first five weeks, with 42.5% of white people receiving the jab compared with 20.5% of Black people in the group. Another study from November 2020 found that participants that self-reported as Black, Asian, Chinese, Mixed or Other ethnicity were almost 3 times more likely to reject a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves and their children than White British, White Irish and White Other participants.

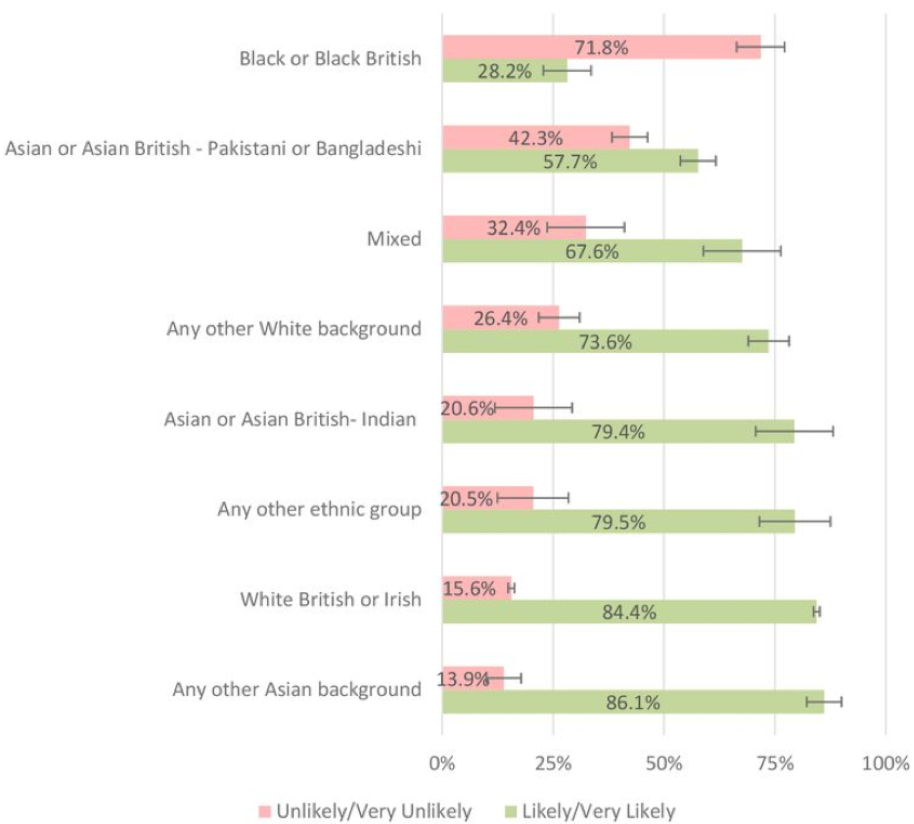

A key challenge to successful uptake of the vaccine is hesitancy. A study looking at the predicators of Covid vaccine hesitancy in the UK household found that vaccine hesitancy was particularly high in Black (71.8%), Pakistani/Bangladeshi (42.3%), Mixed (32.4%) and non-UK/Irish White (26.4%) ethnic groups. The main reason for hesitancy were fears over unknown future effects, concerns as to the speed at which the vaccine was developed, and fears of permanent damage to their bodies.

Willingness to be vaccinated in the UK Household Longitudinal Study by ethnic group (Source:Robertson et al, 2020)

Indeed, hesitancy to take vaccines is on the rise globally, but there is a deep-rooted mistrust of vaccine-related research amongst Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups. Black people have a long history of poor medical treatment and the hesitance around the Covid vaccine should not come as a surprise. Scepticism of vaccines by Black people is not just another anti-vaxxer response. There is a long legacy of unethical drug development practices which have negatively impacted Black, Asian and minority ethnic people just some of which include:

John Quier, a British doctor working in rural Jamaica, freely experimented with smallpox inoculation in a population of 850 slaves during the 1768 epidemic.

J Marion Sims, an American physician in the field of surgery, perfected his surgical techniques by experimenting on enslaved Black women without anaesthesia.

The ‘Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis in the Negro male’ ran from 1932 for around 40 years and none were actually treated for the disease even after treatment became available.

Eugen Fischer conducted sterilisation experiments on Herero women in what is now Namibia in the early 1900s. His experimentation was largely done on mixed-race offspring in order to provide justification to ban mixed-race marriages.

Depo-Provera, a contraceptive, was forcefully tested on Black Zimbabwean women in the 1970s.

Pfizer’s carried out meningitis testing in Nigeria in the 1990s which killed eleven children (others suffering blindness, deafness and brain damage).

AZT trials were conducted on HIV-positive African people by U.S. physicians and the University of Zimbabwe without proper informed consent. The drug tests included 17,000 women to prevent mother to child transmission of the disease but half received a placebo, making transmission likely. As a result, an estimated 1000 babies contracted HIV/AIDS although a proven life-saving regimen already existed. Testing ended in 1998 after they announced they had enough information from Thailand trials.

Such events continue today. In Africa, there are serious concerns about informed consent and research practices, the latest example being the malaria vaccine trial run by the World Health Organisation in Malawi, Ghana and Kenya and has been criticised for committing a serious breach of international ethical standards. Moreover, it was only in April of last year that two top French doctors said on live TV that coronavirus vaccines should be tested on poor Africans who don’t have access to healthcare. These historical events have not occurred in isolation, more generally, Black people continue to be the victims of poor and neglectful medical treatment such as the reluctance to give Black people pain medication for the same conditions as white people. They report being less likely to have been involved in decisions about their care and less likely to have received an explanation of treatment that they understand. Black mothers have worse outcomes during pregnancy or childbirth than any other ethnic group in England. According to an inquiry, Black women are four times more likely to die during pregnancy in the UK than their white counterparts. MBBRACE, authors of the inquiry, note that this is the result of a lack of culturally appropriate care, complications around immigration status, and structural biases around ethnicity. Hannah King, a midwife who is part of the Midwives Against Racism collective, recently told CNN that these biases start in medical school training where white is the default in textbooks and on mannequins making it harder to identify certain issues on darker skin tones.

The NHS Insight and Feedback team produced three short films which share the experiences of Black, Asian and minority ethnic people to help providers and commissioners understand how perceived bias, poor communication and dignity issues can leave Black and minority ethnic cancer patients with poorer patient experience than white British people. A woman in the Bias film discusses how something as simple as a warmer introduction and a handshake could have put her and her husband at greater ease during a cancer diagnosis. In the Communication film, patients and advocates urge healthcare professionals to be more aware of the greater risk of prostate cancer among black men and initiate conversations that could lead to earlier diagnosis. Patients in the Dignity film felt their needs were simply not catered for when they were not offered wigs or compression bandages to suit their hair and skin colouring.

Learning from the experience of BME cancer patients – Bias

Surveys have shown that more information on vaccine trials could mitigate some of the hesitance around vaccines. A poll by the Royal Society for Public Health found that while 57% of Black, Asian and minority ethnic people would take the vaccine, of those with concerns, 35% said they would consider changing their mind if given further information.

In research, the public are often portrayed as a group to be manipulated to change their behaviour, rather than as stakeholders with knowledge and reasons which warrant respectful attention. The lack of trust due to the historical precedence can only be overcome through the involvement of black scientists, doctors, and public health professionals and a clear message about the vaccine via local community organisations. To prevent inequalities in uptake, it is crucial to understand and address factors that may affect COVID-19 vaccine acceptability in ethnic minority and lower-income groups who are disproportionately affected by COVID-19. The most effective way is through local community groups, specifically, Black, Asian and minority ethnic-led organisations.

Harriet Washington (the writer of Medical Apartheid) notes, Black people have historically been key to the development of medical research and in order to change the mentality of those who view medical research as a white province, this history needs to be rewritten. For example, an African slave named Onesimus (birth name unknown) taught doctors in America how to do a variolation – early vaccinations – procedures that were commonly done in Africa and China and Dr Louis Wright, an African American, revolutionised smallpox treatment during WWII. More broadly, there requires an acknowledgement of the links between the impacts of Covid-19 and structural racism because until the factors which create vulnerability in the first place are tackled, these patterns will continue.

Information regarding the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines must therefore be communicated clearly to the public. Some key resources for individuals and organisations are provided below:

COVID-19 vaccination: guide for older adults - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

COVID-19 vaccination: what to expect after vaccination - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

COVID-19 vaccination: why you are being asked to wait - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

NHS frontline staff have recorded messages to explain how the vaccine is given and how they work which can be shared via social media:

Dr Mohammed Abdul-Latif speaking in Arabic

Discharge Coordinator Tazmina Ahasan speaking in Bengali

Clinical Lead for Therapies Sangita Patel speaking in Gujarati

Apprentice Nurse Kasia Kurkowiak-Jolley speaking in Polish

Cadiology Consultant Dr Hamandeep Singh speaking in Punjabi

Maternity Assistant Stefania Vailescu speaking in Romanian

Specialist Speech and Language Therapist Lorena Gonzalez speaking in Spanish

Healthcare Assitant Vivian Motana speaking in Swahili

Consultant Cardiologist Dr Muhiddin Ozkor speaking in Turkish